Memory field

in ARCHITETTURA | architecture

The mutations, determined by the “socialisation” of the places of culture, have, in some way, changed the conception of the museum as well as its policy of management. What, firstly, was a place of observation, culture and contemplation for a selected middle-class public, constitutes today an element of education and mass-amusement thanks to the entry of a vast heterogeneous public (tourists, schools, organized trips,..). This in its turn has attracted sponsor and mass-media. Thus, the building-museum as built is not only constituted of traditional expository rooms but also of by rooms for temporary expositions, auditoriums, book-shops, libraries, mediateche, bars, restaurants and points of sale at service to the museum. The new “secular temple” of the reformed and popular art becomes a more efficient media-channel to make known to the outside a city, to show the economical potentials of a region, as well as to parade the social-cultural policies of a country. Although the architecture has any power to substitute itself to the history, for sure it has the one to help human beings to understand it. Therefore, Nicola Desiderio, editior in chief of Arcomai has submitted an interview to the winner group to the international competition for the Estonian National Museum of Tartu, sure that from the answers of Dan Dorell, Lina Ghotmeh and Tsuyoshi Tane it could come out useful elements for the debate on the contemporary architecture and to the relationship that bind the “work” of the human being to one’s habitat

© Dorell, Ghotmeh, Tane l The roof projects itself towards the open space; the “expository bridge” on the Raadi’s Lake.

Nicola Desiderio. Nowadays, museums can’t be conceived as places in which are saved the memories of a near and far past, especially in an age in which the contemporary society – widely diversified from the social-cultural viewpoint and anymore interested to receive by the visit to a museum a simple emotion – it expects by the museum a real enrichment of knowledge. In this context, the new MNE in Tartu lends well itself to this narrative as it precisely tries to tell something more than the single object that will be exposed inside it: the refound freedom of Estonia; a past “unintentionally” common to other countries but lived fighting to safeguard their own dignity, identity, language and tradition; a “collective” history – unfortunately not very much known – that now more then before doesn’t regard only one country but a the whole continent, a part of the world that has suffered in silence for decades a devastating and cruel regime as the Soviet one; populations that have lived on their skin the foulness of history and, who now feel themselves – with a stronger the soul – to build on the rubbles of the events a different future. In which way your project has taken into account these aspects?

Dan Dorell – Lina Ghotmeh – Tsuyoshi Tane. As you mentioned the emplacement of this National Museum in this Part of Europe, in the Baltic countries, opens up already for the possibility to deal with a whole discourse of a common ‘collective’ history that these countries have lived. It gives a unique opportunity to put forward on a broader level stories and memories of places that are less known in the dominant story/image of what is bounded as the “European” culture. It is also the possibility to deal through this one example with this post-soviet period and its resulting spaces especially if these countries are now able to continue their own story independently. It is important to mention here that we are only able to talk about this discourse on such a broad level because of the typology that we have in hand to build here in Estonia (a national museum) as well as because of the scale of this typology (28 000 m2 compared to a 1.3 M inhabitants).

From a broader scale to a more specific one, this National Museum is able to touch upon this general story and develop it spatially through its sensitivity to its assigned site, the Raadi site. It tries to address specifically the spatial and urban configuration of the elements on this site with an awareness of their historical (post-soviet) and socio-political implication. From the most present (spatially and emotionally) element, a prior war airfield, on the site the museum takes off to transform its meaning. Through this first established relationship it gains a poetic and unique spatial configuration. It uses the scale of the same element that has once led to the degeneration of this East part of the city to urbanely regenerate it. Breaching this possibly interpreted as a monolithic ‘building’, the museum’s spaces sensibly break through in different ways to address the historical buildings that exist on the site (the Restaurant becomes a detached element surrounded by trees penetrating the ground of the museum and visually linking to the Distillery, the old ENM/ The cyclists cut through underneath the building / the exhibition differentiated experiences…).

In this sense, the Museum can be conceived as the Estonian call it the ‘House of Estonia’ as it is focusing on the history and the local reality specific to this nation but it also goes beyond the ‘National boundaries’ to touch upon the story of the area in which it is located as well as outside of it.

N.D. In the article written for the Finish architectural magazine ARK (No. 1/2006) has mentioned a polemic (not only architectural) triggered by some “oppositions” to your project. In which terms have been put such critics?

DLT. The Museum addresses a very sensitive element existing on the Raadi site. A war airfield emotionally charged with painful memories of years of Soviet occupation that the Estonians have suffered through. This Urban element could not have been ignored, and the fact that the museum deals with it has emotionally touched Estonians and initiated some polemics on that subject. While some nationals were rather for ‘erasing’ this memory and ignoring it fearing our intervention to be monumentalizing a painful soviet occupation other Estonians saw our intention with this museum to deal with their history, a move towards the future, a transformation of the perceived ‘negative’ meaning of this airfield into another meaning that will be given through the public platforms initiated in our intervention. But also a possibility to create a dynamic National Museum that does not close itself into its boundaries instead it constantly recreates its meaning and opens for a continuous construction of this ‘National identity’. In this sense, we consider that the museum intervention is achieving its role as a National House that wants Estonians to question its image/identity.

On another level, this intervention brings out another theoretical discourse that deals with the absurdities of a ‘Modernist era’. We can read the existing now dismantled airfield as a utopian absurd space that parallels the ‘continuous monument’ that was once imagined by Superstudio. In this 60-70’s period, their imagined monument was a blunt criticism of an International Style that repeats itself insensitively throughout the urban landscape. Remarkably, through their exaggerated criticism they were able to come up with utopian collages-images that instigated a contrast between an ‘abstract’ space and the daily specific life of people walking on these absurd spaces. In the context of the Raadi site, we are presented already with an ‘absurd’ urban space that cuts through the landscape. And it comes as a single opportunity to appropriate this unique ‘abstract’ spatial quality and transform its meaning with more specific situations, always instigated by the relationships that it establishes with new interventions.

Photo-plan and view of Radii’s area.

N.D. Often, many cities have assigned to single constructions or to museum systems the task to redeem the reality of de-structured, chipped, abandoned urban territories; to re-establish connections; to re-configure relationships; to reveal forgotten pre-existing urban layers, to activate itself as a matrix of urban projects. In the motivations, with which the jury has awarded a prize to your proposal, have been expressed the hope that Tartu, with the realisation of the new MNE, finds in the area of Raadi a sort of redemption to the scared body of the city. In which way does your project act as a structural device of intervention for a context like the one indicated in the announcement of the competition brief.

DLT. We can state that the project is active and being activated as a ‘structuring dispositif’ on two levels. On the first level, we can talk about the new ‘meaning(s)’ that this Museum intervention attributes to the Raadi site. In the present condition, looking at the assigned site, one cannot but notice the urban cut or void that has been created by the prior military airfield, the presence and meaning of which has led to the degeneration of this part of the city. The decision to address this urban void or scar and not to ignore it is an essential step into transforming the meaning of this area and attempting to regenerate it. In this sense, the new national museum does not remain indifferent to its context and develops its own emotional and spatial qualities around the different elements in the site. In a dialectic way, through taking off from the ‘Runway’ it attempts at appropriating it and thus regenerating in a plimpsestical manner the meaning of this airfield, subsequently regenerating that of the whole Raadi area. The intervention initiates then the ‘Use’ of this platform and its appropriation by Estonians. It is no longer, only about a war airfield, witness of years of occupation, but about the roof and ground of the ethnological Museum, an extension of it, a public platform, an art platform, or a land-art extending to an infinite space.

The museum appropriation of this airfield, which in itself can be perceived as an ethnological object, takes it out from the independent ‘box’ standing on the ground to give it a larger urban scale and thus a regulatory impact on its surrounding area, opening up for a ‘special’ (new) urbanization process; a process that would allow this museum to live with the life of the city. This Urban task is not an easy one, it is not only limited to the success of the Museum and the activities it can initiate but it is also dependent on a conscious planning of the area around it. The challenge will be to avoid, once the value of the land has been raised, falling into the forces of a global economical market that would push for unregulated commercial developments. And here, the effort falls on the authorities in hand of the area to have an awareness of their intervention and to thrive for an informed development.

N.D. What strikes travelling through Estonia is the “horizontality” of its landscape: the country is completely flat. Such prerogative is so strong that it loses itself together with the sea that I have always seen from Danzig to Tallinn (crossing the Lithuanian and Latvian coasts) always quiet, flat, and silent. Is it too superficial to state that the solution of the new museum in a single-floor building corresponds to the will to safeguard the morphological characteristics of the place?

DLT. Surely, the morphological aspect of Estonia and specifically that of the Raadi site is one of the aspects that the Museum is sensitive to. But at the same time we cannot reduce the whole intervention to this parallel only as the process of designing this museum was a layering of different parameters: the history of the site, the existing airfield, the relation with existing buildings, the internal logic of the museum …

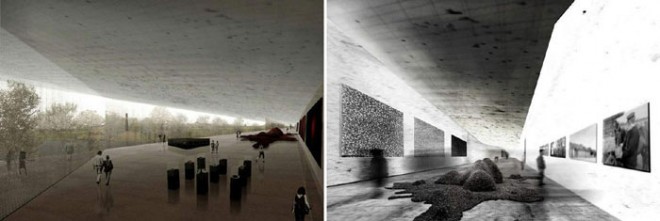

The Museum building formally fits nicely with this horizontal spread and does not contradict the aesthetics of the landscape. This horizontality is expressed in different ways and scales. While the building can be imagined from the plan as a large scale intervention, it shifts in scale in section for a lower profile that horizontally disappears as a line in the surrounding landscape. Moving from the ‘general’ form of the building, the experience of this museum can be described as a layering of different horizontalities. From the longitudinal experience of the exhibition spaces that utter this horizontal space, the visitor exits up into another horizontal ground, the existing ‘Runway’ to finally move back to find herself/himself standing on another horizontality, the ‘roof’ of the building. At this moment, the Museum disappears to become formless, reduced under the grounds onto which you are standing.

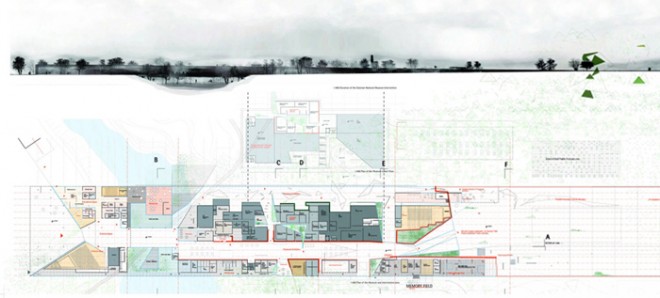

© Dorell, Ghotmeh, Tane l General plan of the project.

N.D. Museums of new generation, organised today according to complex security systems, have become real “safe boxes”: advanced systems of control/alarm, surveillance cameras with closed circuits, thick and greenish antibullets glasses covering almost all the works. Inside them the visitor moves following a network (often labyrinthical) of pre-fixed routs regulated by an articulated series of constraints (for instance: do not sit down, do not take photos, do not talk, …) and obstacles that bring you to follow unconsciously a standard/global emotional program. By this rationalization of flows/files – that orders the museum-machine intelligently – emerges in a worrying way the fact that an art-work is contemplated on an average of no more than 30 seconds. Besides, it must be added that, before, during and after this experience, the visitor can undergo also an elevated quantity of information that, if from one side this introduces the visitor to the exhibited ‘art’, it could likewise produce (dangerously) an excess of messages able to exclude the contact with the original object, if it doesn’t also arrives to twist the meaning that it bears. On the design level, in which way have you dealt with these aspects?

DLT. It is true that Museums, ironically like shopping malls, airports or any large public ‘institutions’ are nowadays dictated by fix prototypical parameters that utter the user’s experience in a fixed way. The challenge in this context is to avoid making out of this museum another ‘typical’ museum journey where, even if the objects exhibited differ, they end up having, due to the resemblance of the promenade, the same memory in our minds as ones exhibited in many other museums. In the case of our proposed Estonian National Museum, we can state that the Museum tries to break from this prototype by engulfing other ‘parameters’ into its own making. It tries not to be an independent ‘pavilion’ that would easily fall into having its ‘functional program’ and its prototype as its only guide into the making of its spaces.Through linking to the existing structures on the Raadi site, a contradiction is already initiated to the prototypical ‘controls’ that are imposed on Museums. The internal logic of the Museum is differentiated here to follow an external, ‘longitudinal’ force that enriches it and takes it out from its typical prototype. Through linking to the existing platform, for example another entrance is initiated; public activities are distributed on different zones of the museum and are no longer capitalized on one end. Another issue that allows us to differentiate this museum’s experience from other museums is the particularity of its activities and objects. Fortunately, the objects to be exhibited are outside of the international material network of what are judged to be valuable objects. They are only valuable because of the stories they want to tell about the Estonian people. This opens up for another less typical and restrictive way of display. This display would develop then by a multi-disciplinary team collaboration who would study the meaning of these objects and the particular stories that they want to tell.

N.D. In the future, since the exhibited works in museums (especially the great masterpieces) will not be visible anymore – maybe for few seconds and however without our bare eyes – the tendency, indicated by those museums that have developed their own commercial activities, goes towards the direction to substantiate the visitors with ‘something else’. Thus, for these palaces the “model’” looks like orientated to references as: the “museum-topic” (a mix between a museum and Theme-park); the “museum-mall” that finds its own symbolics in the underground commercial centre; the “museum-monument” (see: Guggenheim di Bilbao); the “museum-chain” or “museum-satellite” that, inside an internal/global network, overworks the circulation of its products to follow the cultural consumption’s logic; and the nephews of the France’s “eco-musèes” (museum-performance, museum-territory, …) that all together contributing to diffuse the civilization of quotations and amusement. Although architectonically varying, all of these variants become an expression of a “policy of management” that wants places of culture – hus museums – to be economically productive, as far as those who direct them are managers, entrepreneurs, lawyers, notaries, experts in communication…. The new MNE risks to be swallowed up by this logic in a period in which Estonia (especially Tallinn) seems to have understood by now (since some years and with success) that the market of tourism and urban-marketing are speedy/winning formulas for the economical “rilancio” of the country? The choice to locate shops, cafés and bars pertinent to the museum into the existing buildings-depot of the ex-airfield is focused to hold separated the functions of the museum from the commercial ones?

DLT. We have to admit that this is the reality of the Museums in these days, as they are becoming products of a capitalist mode of production. The challenge is not to ignore these commercial spaces but to deal with them to create ‘other’ and unique spaces in this museum. The reality is that nowadays, these activities do ‘attract’ people, and the issue is how do you introduce them in the museum and work on their relationship with other activities so the museum doesn’t transform into a hypermarket. It is a subtle balance between the economic capital and the cultural capital of the project that would create its success.

Adding to this is the spatial and sensorial experience that one should create of these activities so they do not remain abstract commercial spaces, devoid of any quality. As an example, the Restaurant in this ENM is an internal outside space of the museum where, even within the biggest structure of the building, has an independent experience as it is surrounded by trees and giving out to the existing buildings. In the same way, what we proposed on the existing buildings works on this double edge of (cultural and commercial). The distillery which used to be a Vodka distillery can become a Vodka Museum and special Vodka seller. The old ENM stays as an Archiving place but integrate other functional activities that would link it through a rout network to the new intervention. The existing adjacent Cellars can constitute an extension to the educational activities in the museum as well as house future artisans work. The development and economic regeneration of this area would then be possible through assigning ‘normal’ mixed functions to the existing buildings.

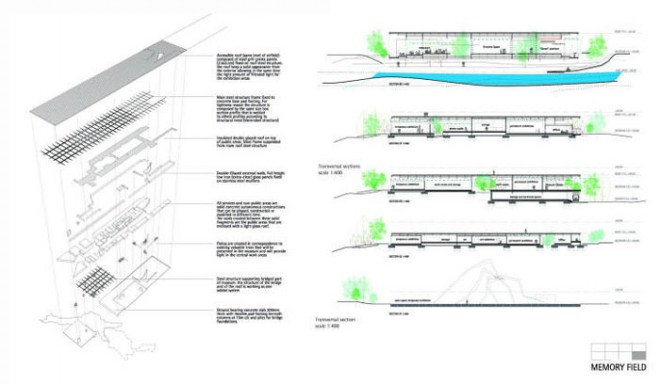

© Dorell, Ghotmeh, Tane l Layers that constitute the platform and cross sections of the building.

N.D. By the analysis of some significant cases, it argues that the museum’s architecture expresses today a culture dominated by the perverse logic of the “museum-monument” – that is definitely the “monument-to fill up” – in which the visitor seems attracted more by the wrapping than by what it contains. In opposite to the tendency to Success-stories – projects of recent known architectures, I consider the project of the new MNE particularly brave, as it shows the choice to avoid to be an invasive element of surprise, breakage and seduction. On the contrary, it shows itself as expression of a sober and controlled spatial program that in its longitudinal development makes the building seem – if I may – an airport or better a terminal that – although slightly sloping towards the sky and thus leading to a runway – reveals itself as a big hall/window open to the outside and oriented towards the built area, as well as a “landing track”: an urban check-in, an arrival hall of stay, of reflection. Do you agree with this interpretation? On the functional and accessibility level how is the complex organized?

DLT. First we have to say that it is a Courageous choice by the Estonian ministry of culture to decide to launch this international competition instead of directly appointing a ‘star architect’ that would fit into a ‘global’ predefined market and do another ‘stylized’ monument in the European landscape. So already through this decision, an opening towards a ‘non-signature’ building is initiated.

The Estonian National Museum ‘memory field’ plays on a double edge; on one hand it can be described as a non-building, a non-architecture: – PHYSICALLY and literally in its low profile/section, its refusal to appropriate an architectural style; – SPATIALLY in the variety of qualities of spaces it houses, from private to public spaces (the different qualities of public spaces; the roof, the runway, the internal exhibitions, the restaurant, the auditoriums…). But also in the way it is an open system, and a building that retains an infinite profile through opening up into a runway, a public platform. – and SOCIALLY, in the multiplicity of social readings in which this building can be understood. At the same time that it is an ethnographic museum, it is a popular museum, a public space, a landscape, a land art… a social space that is reflected by a fragmented building.

On another hand, the same reasons that make out of this building a non-architecture render it a monument (or a different definition of ‘monument’); An infinite landscape, a testimonial of public space, or a public monument. In its ‘extending’ scale, this building can be termed as you described it as an ‘urban check point’ that opens up for a silent but at the same time a busy cut in urban landscape. Silent, in its poetic feel and busy with the new urban activities it generates around it. Allegorically, the intervention does resemble an airport, where the tilt of the museum’s roof can be imagined as if Estonia is literally taking off its past.

N.D. The museum’s site – that extends on a surface of 28.000 sqm. with a cost valued approximately to 38 MIL di Euro – will start in 2007 and will be completed in 2011, year in which Tallinn will be the European Capital of the Culture. On the technical level, what the project provides concerning to the purveying apparatus (heating and air-conditioning) and the one of the lighting (diretta/indiretta), considering those particular environmental aspects (climate and light) that characterised this country of the Baltic area? Were these conditions somehow bases for decisions during the planning phase?

DLT. The building as it is designed is trying to save energy and use natural energy to operate. In the same time, the fact that the building is set in a polluted area; Raadi initiates a whole treatment to clean this area. As we know, Museums need a special kind of lighting which could be very energy consuming; we have tried through our project to use the roof of the building in order to provide natural lighting into the museum. Through the layering of this roof and the introduction of controllable louvers we reduce the need for artificial lights. While the permanent exhibition area is between two volumes, with more controlled light; the temporary exhibition is located on the North side of the museum, allowing for a glazed façade and an empty space flexible for partitioning following the exhibition themes that could happen. Technically, we are working with Ove Arup on energy saving techniques. The building will have a high performing envelope. This shall be created by using triple glazed panels and highly insulated opaque elements. The envelope will seek to minimize heat loss in the winter and heat gain in the summer. We will also look to provide primary heating plant, which is friendly to the environment and is technically and financially feasible in the local market.

© Dorell, Ghotmeh, Tane l Ground floor plan with indicated the functions of the environments

N.D. What the “big spider” monument representS in your project? Where is it located and how will it be realised?

DLT. The spider that we illustrated on the roof of the building represents the French/American artist Louise Bourgeois’ sculpture. This sculpture was lately exhibited in the Tate Modern in London. It is put on the roof of our building to show what scale of art intervention can happen on the roof. Comparatively to the volume of the Tate that initiated this unique kind and scale of art intervention, the ‘Runway’ that was appropriated by the museum is meant to initiate, along with other public activities, a unique art that is only possible because of the configuration of this ‘airfield’. Other art works can be done through simple land-art treatment on the runway as the Artist Andy Goldsworthy would do it. In this frame, all of this museum intervention can also be read as a sort of land-art that can be compared to the ‘spiral’ intervention of the artist Robert Smithson.

N.D. The history of architecture of these last decades could be also narrated though museums (for instance: Piano in Paris, Sterling in Stuttgart, O’Gary in Minneapolis, Libeskind in Berlin…) not just with regard to the linguistic tendencies, but to the theory/literature as well as the experimentation of the technological-constructive components. The architects more disinhibited and prepared know that and they have always looked at the museum as a unique opportunity thanks to reach – through a process of “synthesis”, what the architecture needs cyclically to express itself: the “poetics of the space”. Is it possible, considering the successful collaboration that binds you as winner-group of the competition, to reflect upon the international contemporary culture of the project? What emerges as unpublished through your proposal? In which direction do you think is contemporary architecture in Europe moving?

© Dorell, Ghotmeh, Tane l Interior views of the expository hall and gallery.

DLT. It is true that “Architecture” nowadays can be defined by the evolution of Museums. We can attribute this to the fact that these functions like others constitute ‘noble’ projects that are normally assigned by the government. In this sense, there is some means for architectural exploration since the ‘government’ capitalizes on this architectural image. These functions become as well the voice of Architecture, although they constitute a very low percentage of our architectural landscape, they have the possibility that the institutions would legitimize them through transferring their own dominance to them. We can say that our museum delicately addresses these issues. It tries to escape any pretension to represent a whole mono-disciplinary “Architectural” field. As it modestly poses itself in the landscape, it constructs its character through the specific way it addresses its site and the history of its context. It is an intervention that can be said to be an Architectural one as much as Artistic, Abstract or Social. In theory, it crosses different discourses: from a Non-Architectural critical stand that was carried through in the 60’s and 70’s and that continued to be the base of the work of many contemporary Architects … to a more ‘contextual’ stand that wants to respond to the specific site in which it is situated, to end up appropriating a somehow socio-political discourse that wants to deal with post-war remaining in this case transforming post-soviet spaces.

As a team designing this museum, we mention two things. The first concerns the fact that being three architects working on this project we are already trying to go out of this belief in the ‘one’ architect or the ‘genius’ architect. Here, it is more about the collaboration of different Architects. The second issue, that could be unique in our situation is our present world global situation, where we found ourselves as three Architects from different nationalities and formation working together: an Italian Dan Dorell, a Lebanese Lina Ghotmeh, a Japanese Tsuyoshi Tane, and trying to find even in the ‘globalization’ that joined us a specific lens through which we can critically address space in our multiple viewpoints.

Dan Dorell. As an Italian Architect who is born in Tel Aviv, Israel. Dan Dorell has graduated with a MArch from the Polytechnico of Milan, Italy after spending a year on an exchange program at Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow, United Kingdom. In 2000, He received an honorable mention for Sarajevo International Concert hall. Dan Dorell has built his design experience through his work in the last 10 years with renowned International Architectural practices in Milan, London and Paris; Among them Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Paris; Michael Hopkins and Partners, London and recently Ateliers Jean Nouvel in Paris. Since 2005, Dan Dorell is heading a Design Studio along with his partners Lina Ghotmeh and Tsuyoshi Tane in Paris and in London.

Lina Ghotmeh. As a Lebanese Architect who is born in Beirut, Lebanon. Lina Ghotmeh has graduated as an Architect with ‘Distinction’ from the American University of Beirut, Lebanon. Along her educational years she received the Azar Award – a full year scholarship award for Architectural Excellence, Areen Award – a Diploma Project Excellence Award and The Lebanese Order of Architects Honoring membership Award. In 2002, she won the first prize award for a rehabilitation project for a 1km beach resort in the city of Tyr, Lebanon. Lina Ghotmeh has been building her design experience through her work with International Architectural practices in Beirut, Paris and London; among them Bernard Khoury Architects, Beirut; Ateliers Jean Nouvel, Paris and lately Atelier Foster Nouvel, a London based Joint venture between Ateliers Jean Nouvel, Paris and Foster and Partners, London. Since 2005, Lina Ghotmeh is heading a Design Studio along with her partners Dan Dorell and Tsuyoshi Tane in Paris and in London.

Tsuyoshi Tane. As a Japanese Architect who is born in Tokyo, Japan. Tsuyoshi Tane has graduated from Hokkaido Tokai University in Japan during his study spending a year in Sweden respectively in HDK and Chalmers Technological University, Gothenburg. After his dgree in Japan, he took a year study at The Royal Danish Academy of fine Arts, Copenhagen. Along his studies he received the AIJ (Architectural Institution of Japan) Silver Prize for his Diploma project and the Excellence Student Awards in Hokkaido, in 2002, he received the SD Award for The 21st SD Review, in 2003 a special mention for KUMANOKODOU information center competition, and in 2004 the winning project for The 23rd SD Review in Japan. Tsuyoshi Tane has been building his design experience through his work with International Architectural practices in Tokyo, Copenhagen and London; among them Shigeru Ban Architects, Tokyo; Henning Larsens Tegnestue A/S, Copenhagen and David Adjaye Associates, London. Tsuyoshi Tane has also a special interest in the contemporary dance; in 2004 he had collaborated on a dance performance ‘SHIKAKU’ with the Japanese choreographer Jo Kanamori. Since 2005, Tsuyoshi Tane is heading a Design Studio along with his partners Lina Ghotmeh and Dan Dorell in Paris.