Art on the ground: Eduardo Paolozzi

© Thierry Bal I Tottenham Court Road.

The London Underground is not only an efficient transport system, but also an open-air art gallery, in which the functionality of public transport is combined with the beauty of contemporary art, offering the passenger a unique cultural experience that is renewed on every trip. The “Art on the Underground” project, born in 2000, transformed the stations into exhibition spaces, drawing inspiration from the vision of Frank Pick (1878-1941), who was responsible for the development of the corporate identity of the English capital’s underground. Since then, numerous artists have contributed to making the experience of riding the Tube unique. To help passengers discover these works of art, an “Art Map” has been created and is available in stations and online. This map indicates the main works and provides detailed information on each of them. Special maps are periodically created, such as the “Paolozzi Map” dedicated to the Italian-Scottish artist.

Born in Edinburgh, Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005) moved to London in 1945 to study at the Slade School of Art, thus beginning a deep bond with the city. Returning to London in 1949, he became a point of reference on the contemporary art scene, teaching at the Central School of Arts and Crafts and participating in key exhibitions such as “1950: Aspects of British Art” at the ICA and “This is Tomorrow” at the Whitechapel Gallery. His reputation grew rapidly, leading him to receive prestigious commissions in Germany and the United Kingdom. It is precisely thanks to his international fame that, in 1979, London Regional Transport invited him to create a monumental work for Tottenham Court Road station, a project that definitively established him as one of the major artists of his time.

© Thierry Bal I Tottenham Court Road.

© TfL I Sir Eduardo Paolozzi & Duncan Lamb, (c. 1983).

It is a monumental mosaic. A document in images that tells the story of English society of the time. A puzzle of stories within history. As soon as you set foot on the platform, you are greeted by an explosion of colours, shapes and images that envelop you like a kaleidoscope: gears that seem to move, musical instruments that play imaginary melodies, mythological creatures that observe you with curious eyes. There is a vibrant energy in every single tile, an explosion of life that draws you into a fantasy world. Paolozzi wanted to create a work that reflected the soul of London, with its contrasts, its vitality and its history, representing this as a hymn to daily life, popular culture and the limitless creativity of those years. This is why we find references to the nearby British Museum, with its ancient Egyptian deities, but also to the lively Soho district, with its music shops and nightclubs. The mosaics on Tottenham Court Road are much more than just decoration. They are a work of art that invites us to reflect on our society, our culture and our aspirations. They are a legacy that the artist left to the city of London, a work that continues to amaze and enchant visitors from all over the world.

© Flowers Gallery I Euston Station, “Piscator” (3.1m × 4.6m × 1.8m) .

This pop nature of his can also be found outside Euston Station with a bronze sculpture that celebrates not one of the most illustrious heroes of British history but an unusual character: the German artist and theater director Erwin Piscator (1893-1966). The work entitled “Piscator” is from 1981 and represents a large abstract sculpture, also known as “Euston Head”. It is a rectangular cast iron block with sides characterized by silver protuberances and recesses. Although some critics glimpse the shape of a head, for me it summarizes the “gravity” of the director’s thought. In fact, Piscator brought a political and innovative practice to the theatre, reworking the texts in a Marxist sense, as well as revolutionary scenic expedients making use of the most modern stage-technical innovations in the staging (the rotating platform, the treadmill, the multiple scene, etc.); in the cinema he was among the first to include films and projections in the action.

But his theatrical experience is also linked to architecture. In 1927 Walter Gropius designed the “Total Theatre”, perhaps the most important work of the Bauhaus. Designed for the Volksbühne, founded by Piscat, the building translates the director’s theatrical research by imagining a completely flexible scenic space, where the distinction between actors and spectators was eliminated. The goal was to create an immersive experience, in which the audience was an integral part of the performance. To understand this work you have to go around it and perceive this large block of bronze as a fluid volume that contains the thinking matter of a fantastic world where anything can happen.

© Paul Grundy I King’s Cross St. Pancras Station, “Newton After Blake” (3.7m).

After Blake” from 1997 is a bronze sculpture in front of the British Library, not far from King’s Cross St. Pancras Station. The work, inspired by an engraving by William Blake (1757-1827), depicts Isaac Newton (1643-1727) sitting with his gaze turned downwards over drawings and diagrams which he is analyzing with a compass. The statue is on a pedestal that replaces Blake’s rocks, and the body of the English physicist and mathematician is here transformed into a man-machine (robot) to celebrate the “positivistic” relationship (a century in advance) of man and of the machine in the British context.

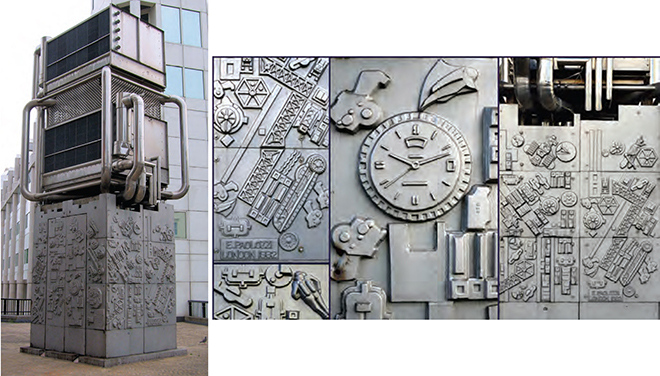

We find this trust in science and technology in the “Cooling Tower” near Pimlico Station. It is a sculpture created in 1982 that hides the ventilation shaft of an underground car park several meters below. Here too the sculptural box is a machine made of metal grates and tubes on a base covered with panels in relief showing elements such as wheels, gears, car parts, butterflies, fish and astronauts. They look like bas-relief hieroglyphics of a totem of an ancient civilization that mysteriously disappeared. These two works are the essence of British culture at the end of the 20th century marked by the architectural utopia of The Walking City by Ron Herron (Archigram, 1964) and the Lloyd’s Building (1978-1986), a masterpiece of “high-tech architecture” by Richard Rogers, along with the dystopian cinema of Blade Runner (1982) and the Mad Max saga of the 1980s. Between these two parameters we can fit art, literature, music and much more. The fate of the innovative European culture of the late twentieth century was undoubtedly British.

© Jim Linwood / wikicommons (left) and George Rex (right) I Pimplico Station, “Pimplico Cooling Tower” (3m × 3m ×12 m).

A few steps from Kew Gardens Station we have “A Maximis Ad Minima” from 1998. The work is located at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew. Its location in a natural context contrasts with the industrial nature of the work, creating a dialogue between man and nature, between the artificial and the organic. In Latin the title means “From the largest to the smallest”. The sculpture invites us to a visual exploration that goes from the macroscopic to the microscopic and summarizes the artist’s ambition to capture the complexity of the modern world, from large industrial machines to the smallest particles of matter. The work, made of bronze and stone, is composed of a myriad of abstract elements assembled in order to create a dynamic composition rich in meaning. Stylized human figures, mechanical gears, pure geometric shapes: everything contributes to creating an image of the contemporary world as a mosaic of constantly changing fragments. We find the same poetics outside the Royal Victoria Station with the monumental “Vulcano”. The work is of impressive dimensions and made of bronze.

© Jim Linwood / wikicommons I Kew Gardens Station, “A Maximis Ad Minima” (1.3m × 2.5m × 1.2 m).

We find the same poetics outside the Royal Victoria Station with the monumental “Vulcano”. The work is of impressive dimensions and made of bronze. The figure of Vulcan is represented while wielding a hammer, symbolizing his activity as a blacksmith and creation. His pose is dynamic and powerful, and the sculpture’s surface is rich in detail that invites the viewer into careful observation. The interpretation of “Vulcano” is open to different readings. Some see the work as a celebration of technological progress, others as a criticism of industrialization and its consequences. In any case, it is clear that Paolozzi wanted to create an artifact that would provoke reflection on our relationship with technology and the future of humanity. There are several versions of “Vulcano” scattered around the world. One of the most famous is located in the National Galleries of Scotland, in Edinburgh.

The abundance of mechanical and industrial elements refers to the technological progress of the 20th century, a recurring theme in Paolozzi’s work. The human figures, often represented as gears or machine parts, suggest a reflection on the condition of man in the industrial era, underlining his fragility in the face of the forces of technology. The juxtaposition of organic and mechanical elements invites us to question the very nature of reality, the relationship between man and machine, and the role of art in representing the contemporary world.

© Luis Veloso I Royal Vittoria Station, “Vulcan”, 1999 (8m × 3m × 3 m).

The sculpture titled “Head of Invention” is located near the Design Museum and is a powerful and thought-provoking piece that blurs the line between man and machine, a prevalent theme in much of Paolozzi’s work. It is a complex and enigmatic work that invites interpretation and contemplation; it is a fitting tribute – if not a manifesto – to the power of human creativity and innovation. It reminds us that even in the machine age, the human mind remains the ultimate source of inventions and discoveries.

Eduardo Paolozzi’s work represents a faithful mirror of the turbulence and aspirations of post-World War II society. His works, characterized by a collage of industrial images, fragments of everyday objects and references to popular culture, reflect a world in profound transformation, marked by contradictions and an uncertain vision of the future. The use of fragments of classical sculptures and historical images refers to the sense of guilt and responsibility towards the past, marked by the two world wars and totalitarianism. The obsession with the machine and emerging technologies, present in many of Paolozzi’s works, reflects both the fascination with progress and the fear of a future dominated by machines and dehumanization.

Through the reworking of images and objects, the artist seeks to build a new identity, a visual language capable of expressing the complexities of the contemporary world. Even the use of images taken from comics, films and advertising testifies to the desire to elevate popular culture to an art form, recognizing its role in defining collective identity. Despite the anxieties and uncertainties, in the artist’s works one can also perceive a profound trust in the future, in man’s ability to overcome challenges and build a better world. Paolozzi, through his works, seems to question the limits of human thought, the fragility of the body and the temptation to replace it with the machine. All this for the simple cost of a subway ticket.